CORE COMPETENCY 2: CREATING EFFECTIVE LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS

As a social justice-oriented individual, I understand this core competency through the lens of justice, equity, inclusivity, and community-building in the classroom. As an educator, I take responsibility for fostering a learning environment that is a respectful community of knowledgeable learners who can learn from each other, not just me, and from whom I can learn as well. Part of how I realize this value is by promoting an active, experiential learning environment. When students are active participants in the learning process, there is a community dynamic in which folks work together, learn with and from each other, and start to overcome a sense of imposter syndrome. A key way in which I create an active learning environment is through the integration of digital humanities activities. In my article “Building a Pedagogical Relationship Between Philosophy and Digital Humanities Through a Creative Arts Paradigm,” I present a number of ways in which philosophy educators can use digital humanities teaching methods in our teaching to enhance philosophical learning. So, I understand this concept as both a social justice issue and one that invites interdisciplinary approaches to learning.

As a social justice-oriented individual, I understand this core competency through the lens of justice, equity, inclusivity, and community-building in the classroom. As an educator, I take responsibility for fostering a learning environment that is a respectful community of knowledgeable learners who can learn from each other, not just me, and from whom I can learn as well. Part of how I realize this value is by promoting an active, experiential learning environment. When students are active participants in the learning process, there is a community dynamic in which folks work together, learn with and from each other, and start to overcome a sense of imposter syndrome. A key way in which I create an active learning environment is through the integration of digital humanities activities. In my article “Building a Pedagogical Relationship Between Philosophy and Digital Humanities Through a Creative Arts Paradigm,” I present a number of ways in which philosophy educators can use digital humanities teaching methods in our teaching to enhance philosophical learning. So, I understand this concept as both a social justice issue and one that invites interdisciplinary approaches to learning.

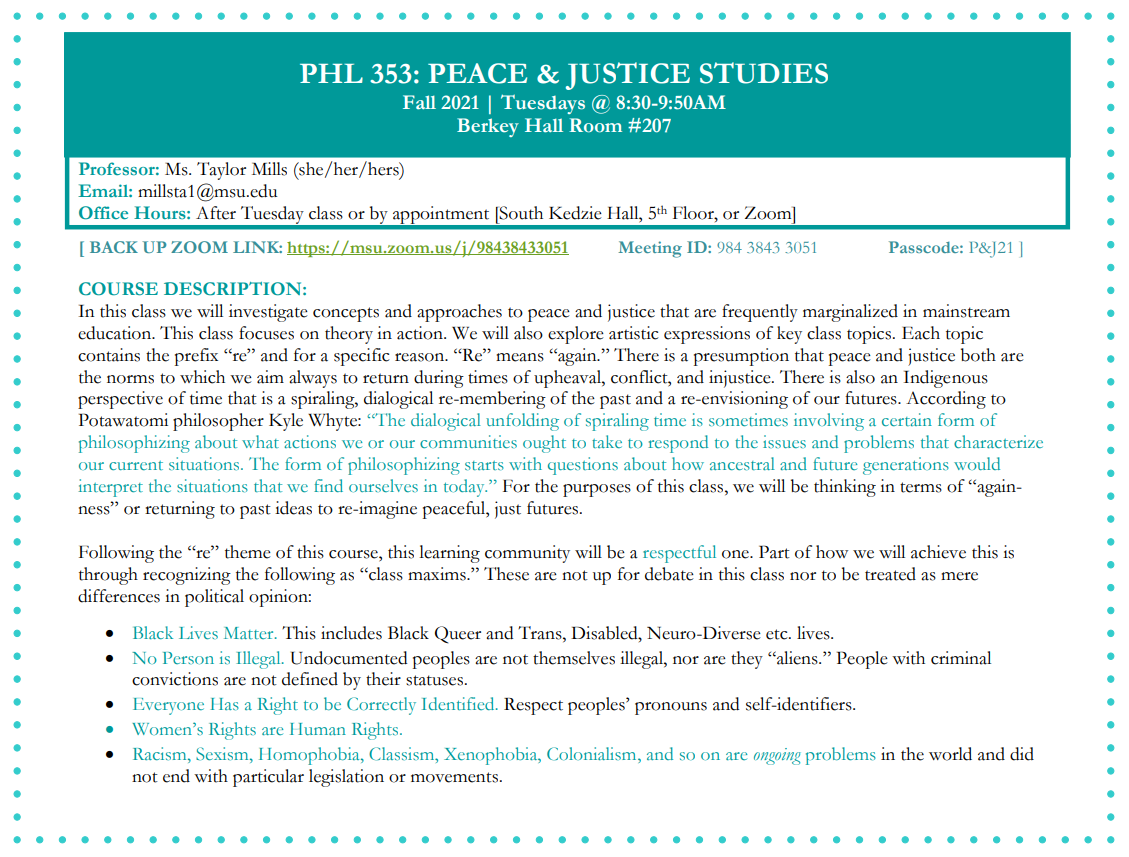

ARTIFACT 1-SYLLABUS: In my most recent syllabus for PHL 353: Introduction to Peace and Justice Studies (and my previous syllabus for PHL 354: Philosophy of Law), I put my commitments to cultivating a just, respectful, active learning environment front and center on the syllabus. Here is what I stated:

ARTIFACT 1 RATIONALE: There are several reasons why I wrote this portion of the syllabus in this manner. The first was to “put my money where my mouth is.” I think it is easy as a white faculty person to say I care about diversity and inclusion, but still center white voices in the structure and content of a course. To avoid this pitfall, the majority of the assigned readings on the syllabus were not white, and the design of the course was grounded in Indigenous approaches to time, knowledge, and justice. Specifically, Potawatomi scholar Kyle Whyte’s concept of spiraling time, a forward motion with careful and continuous re-engagements with the past, inspired the course’s focus on memory, and “re”-evaluations of core concepts in peace and justice. Additionally, the syllabus includes a tailored land acknowledgement; I chose not to copy and paste the MSU acknowledgement but rather adapt it to accurately reflect where I am in my relationship to colonialism and Anishinaabe communities. By modeling a form of self-accountability, I aimed to instill this in my students.

Finally, the “class maxims” are explicitly aimed at embodying the commitments to diversity, equity, inclusion and so on. By including these maxims on page 1 of my syllabus, I aimed to make clear from the beginning that my classroom is a safe space in which communities’ identities and experiences are not matters of political opinion or debatable.

ARTIFACT 2 [& RATIONALE]: CCT Institute Workshop “Creating Effective Learning Environments: Five Easy Steps to Peer Instruction” In brief summation of this workshop, we discussed a method of active learning through polling in peer instruction. The model offered to use was that educators pitch a question or problem to students, who then respond to the prompt with a poll or clicker. After the responses are recorded and shared, students discuss with each other whether they still agree with their submitted responses. After some discussion, they re-submit an answer. The answer usually is correct and held by the majority. This process demonstrates that students are a knowledgeable community, and through co-instruction, they can learn from each other. In the workshop we were presented with this model and then participated in it ourselves with questions about Newton’s Third Law of Physics, the play Middlesex, and seasons. A key feature of the process was upon second review of the question, the questions were framed in a different way to elicit conversation via Bloom’s taxonomy.

REFLECTION: In course evaluations and in direct comments I have heard from students that the course did feel like a safe and inclusive environment, which was one of the most gratifying things to hear as a social justice-oriented educator. I have not had any students comment on (negatively) or complain about my class maxims, which I take to be a good sign both in the way I have them framed and in the way students are growing as open-minded learners.

Despite these successes, I still have plenty to work on! While I focus heavily on Indigenous, Black Feminist, and queer scholars, I am not as knowledgeable in Latinx/Hispanic, Asian, Middle Eastern, and other racialized communities’ experiences both academically and interpersonally. Often I and other white scholars focus our DEI efforts on anti-Black racism, and while this is paramount, it is not comprehensive of all racialized experiences. Similarly, I know little about disability justice both as a body of scholarship and as an educator. I a committed to learning more about how to make my classroom more accessible, but still have work to do.

Regarding the CCT Institute Workshop on this core competency, I was inspired by the polling system. I saw it as useful for a “temperature check” of how students were feeling and understanding the content. I thought that the offered active learning process of Problem – Poll – Discussion – Re-Poll was an innovative way to engage students in discussion. I like how it reinforces my own commitment to making students feel empowered, knowledgeable, and collaborative in the communal learning process. When reflecting on this activity at the Institute, I noted that applying this method to philosophy could be useful to balance out the challenge we often face of having a few “talkers” and a few shy students who avoid participating. My starting with a poll, there is a less daunting invitation to participate and also a buffer for the talkers to “listen” to their peers first before speaking. Especially during times of online learning, I am interested in applying this polling method for a future lesson plan.

SOURCES:

Whyte, K. (2017). “Indigenous Climate Change Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene.” English Language Notes, 55(1-2): 153-162.

Bloom’s Taxonomy Resources: https://www.uvic.ca/learningandteaching/assets/docs/instructors/for-review/; https://www.wcupa.edu/education-socialWork/assessmentAccreditation/documents/Blooms_Taxonomy.pdf

Peer Instruction Resources: https://cwsei.ubc.ca/resources/instructor/prs; https://peerinstruction.wordpress.com/author/peerinstruction/; https://ctal.udel.edu/2016/05/12/techniques-for-peer-instruction/

CORE COMPETENCY 3: INCORPORATING TECHNOLOGY IN YOUR TEACHING

Incorporating technology in teaching has transitioned from being a cutting edge concept to a modern necessity, especially through a global pandemic. As a digital humanities scholar and teacher, I say that digital humanities is humanities, and the hyper-distinction it receives is becoming less necessary in our digital world. Therefore, technological competency in teaching is an essential means of helping students learn, study, access content, and engage with material and digital content. Technology is also more than just computational and digital tools; technology technically means “the sum of any techniques, skills, methods, and processes used in the production of goods or services or in the accomplishment of objectives, such as scientific investigation.” Thinking about teaching as a sum of techniques and methods to accomplish learning is about inherent to pedagogical development as anything else. At the core, I would argue that this competency requires creativity, intentionality, and innovation.

ARTIFACT 1-PUBLICATION: In the summer of 2019 I conducted research and wrote the now published article “Building a Pedagogical Relationship Between Philosophy and Digital Humanities Through a Creative Arts Paradigm.” In this article I explore various methods that the digital humanities has to offer teachers, particularly philosophy educators. These methods include: distant reading, relational/network analysis, mapping, gamification, modeling, and exploratory play. Integrated into philosophy classrooms, I argue that these methods can 1) help make philosophy relevant and accessible, 2) foster active learning and engagement, 3) establish equitable, collaborative participation, and 4) encourage creativity. I make this argument by conceptualizing the aims of philosophy education as a kind of creative art. Here is an abridged version of the abstract for this paper that captures these endeavors best:

Through a proper pedagogical framing of both fields, I argue that philosophy educators would benefit from building a pedagogical relationship with digital humanities. First, I outline digital humanities methods and teaching practices, then I identify several core educational aims and teaching methods in philosophy, which I conceptualize in terms of a creative art. Ultimately, I argue that digital humanities practices would enhance philosophy’s education aims by making philosophy more relevant and accessible to students’ needs, by fostering active learning, by establishing more equitable, collaborative participation, and by balancing skill-development with philosophical creation.

ARTIFACT 1 RATIONALE: I have included this paper in my portfolio because the process of researching and writing it helped me reflect carefully about the relationship between teaching, technology, and philosophy. I distilled the main pedagogical methods in philosophy to lecture, discussion, group work, and writing, and analyzed each in terms of strengths and weaknesses. While all have their merits, it was a valuable experience to unpack how incorporating technologies into each method would enhance the learning experience by addressing some of the weaknesses. For example, lecture is still one of the most popular teaching methods among philosophers, but this method is not an especially active form of learning. Even by integrating clicker questions and polls throughout the lecture to check-in with students is an easy way to integrate a more dynamic interaction with the lecture. Another example I presented was with writing, a fundamental skill and method in philosophy. Writing is often designed to practice argument construction; however, writing arguments can be an abstract endeavor that students struggle to grasp. By integrating technologies like building digital arguments through persuasive websites, students collaborate on the art of argument-construction through more tangible methods:

Consider the simple example of wanting students to create an argument, the most prominent of philosophy educators’ aims. An argument requires careful reasoning, powerful points of persuasion, strong supporting evidence, mindfulness of the intended audience, strategic organization, and conscious protection against possible objections. None of these elements have to be delivered in a purely cognitive or linguistic manner in order to be effective. Now consider the process of building a website on a particular topic. Website builders must identify their target audience and tailor the site linguistically, visually, and structurally to their audience, i.e., strategically organize. The content on the topic needs to be supported and draw from reputable sources in order to be taken seriously amidst the sea of false information. Supporting evidence with graphics, audio clips, and video all enhance the experience and further the proposed interpretation of the site’s topic. In essence, building a website requires a high degree of careful reasoning, decision-making, and reflection, a process that embodies the aims of experiential learning, as well as many of the key aspects of creating an argument. I propose categorizing a website as a kind of digital argument.

Ultimately, this article demonstrates my learning as a digital humanities scholar and philosophy educator about technology and pedagogy. It captures my own thoughts on the topics and my suggestions to fellow philosophy colleagues who may be interested in incorporating more technologies in their teaching.

ARTIFACT 2-GRADUATE CERTIFICATE IN DIGITAL HUMANITIES: The Graduate Certificate in Digital Humanities has three core requirements, one of which is pedagogical. Graduate students are expected to “engage with the critical work of planning and delivering DH instruction.” According to the program handbook, there are variety of ways to satisfy this requirement, including taking the DH861 Digital Humanities Pedagogy course, GAships GAships that involve DH pedagogy, or teaching a DH course. For this requirement, I deliberately integrated digital humanities into my seminar in Teaching for Philosophy, producing an Introduction to Digital Humanities Syllabus and an Introduction to Philosophy syllabus that incorporates digital humanities methods.

ARTIFACT 2 RATIONALE: I’ve included this certificate as a whole because all of the certificate requirements have taught and trained me in technology-based learning and scholarship. The pedagogy component is especially relevant to this core competency because I spent a semester developing syllabi that integrate technology into DH and philosophy classrooms. The experience expanded my teaching skills and technological skills, but it especially expanded the nexus of these two.

ARTIFACT 3 [& RATIONALE]: CCT Institute Workshop: “Incorporating Technology in Teaching: Design Space Activity.” In the CCT Workshop, we were put into groups and tasked with designing a learning activity with a chosen technology to achieve a learning objective for a general education course. We were assigned Botany and the learning objective was to have students “communicate the significance of a figure or data set to a non-specialist audience.” The technology options were audio/video, Google Documents, and Twitter. We chose twitter because it is open access and accessibility-friendly with a wide audience. We imagined using this technology to data mine, curate information, and geo-map. To reach our learning goal we created a learning activity in which students would be assigned a class hashtag of #botany4every1 and the task of going out into the neighborhood, identifying a plant, share a little bit about the plant with the 280 characters, and include the hashtag. We knew this would help accomplish our learning goal because 1. students were limited to only 280 characters, so they must be succinct and straightforward with the information they share about their plants; 2. students knew their tweets would be publicly accessible so they had to think about communicating what they knew in to a wider non-botanist audience; and 3. the shared hashtag would create a collection of tweets about botany accessible to a wider audience that could increase public interest in the topic.

REFLECTION: Reflecting on this core competency, I think I am both uniquely experienced with my background in digital humanities, and yet surprised by how much more there is to learn. From the workshop I was most struck by how broad the term “technology” can be. My main takeaway from that workshop was that the bounds of what constitutes a technology are pretty open so be creative! This concept of creativity is, I think, central to teaching and learning, especially with technology. Changing students’ perspectives and approaches to new material is essential and enhanced with technology. Technology itself can be as simple as a string of lights to as complex as a javascript. Having taken the workshop first before publishing the article, I noticed that a reflection I wrote at the end of the workshop planted the seed for the article. On the reflection worksheet for the final question about how I can apply what I learned for my own class to enhance the effectiveness of teaching and learning I wrote that I could have students physically and digitally represent aspects of philosophical arguments through technologies as simple as blocks to as complex as digital network mapping. This inspired an emphasis on creativity and active learning through digital humanities methods that would become my publication. The conclusion I draw from this core competency is that I will always be passionate about incorporating technology in teaching, and I hope to continue being creative myself with how I do so.

SOURCES:

See publication Bibliography; see also Tech @ MSU resources: https://tech.msu.edu/service-catalog/teaching/, https://www.educause.edu/eli, https://hub.msu.edu/, https://digitalhumanities.msu.edu/, http://www2.matrix.msu.edu/about/

CORE COMPETENCY 4: UNDERSTANDING THE UNIVERSITY IN CONTEXT

I am the type of learner who needs the big picture before jumping into small details, and I see the core competency of understanding the university in context as just that. In order to be an effective teacher, one must understand the big university picture, or context, in which they teach. Understanding the values of the institution, the kinds of students who come to the institution, and the goals the institution has for its students are all key for effective teaching, because they tell us what we should focus on in our classrooms, what to expect from our students, and what the institution will expect of us.

I am the type of learner who needs the big picture before jumping into small details, and I see the core competency of understanding the university in context as just that. In order to be an effective teacher, one must understand the big university picture, or context, in which they teach. Understanding the values of the institution, the kinds of students who come to the institution, and the goals the institution has for its students are all key for effective teaching, because they tell us what we should focus on in our classrooms, what to expect from our students, and what the institution will expect of us.

ARTIFACT & [RATIONALE]: CCT Institute Workshop “Institutional Types, Mission, and Teaching Statements” [& Teaching Philosophy Statement] In this workshop, the presenters gave us an overview of the university structure, and the different kinds of institutions. Then we were presented with five different examples of mission statements on teaching. The Research Institution (MSU) prioritized inclusion, interdisciplinarity, and, unsurprisingly, high-quality research. The Comprehensive Public University (Grand Valley State University) included an emphasis on diversity, collaboration, academic excellence, and community impact. The third example, a Liberal Arts Institution with a Religious Background (Calvin College) talked about cultivating one’s calling or vocation within the Christian tradition, and teaching as an “intentional and systematic engagement of students in vigorous liberal arts and professional education.” The Fourth example, a Minority-Serving Institution (Howard University) held similar principles as the other institutions but with a particular emphasis on Black students being historically aware and compassionate about discovering solutions to human problems. Lastly the Community College example (Jackson Community College) offered a simple focus on inspiring students to succeed and meet the needs of communities with teaching that is active and assessment-oriented. (We did not spend much time on for-profit institutions.)

REFLECTION: Learning about the different values of each kind of institution was a helpful activity. While there was significant overlap, the differences among the offered examples helped me think about what my own values are, and where I might want to work in the future. Upon reflecting, I realize that I have had a relationship with most forms of institution at this point. Presently I am attending a Research Institution as a graduate student, but prior to MSU I went to Hope College, a Liberal Arts College with a Religious Background, for my undergraduate degree. I also grew up in a town with a small Christian Liberal Arts University. While in high school I received credits at a Community College, and this summer I will be working with Tribal Colleges on a digital archive project. Aside from the Comprehensive Public University, I have had experience with all of these institutions, but I had not reflected on their differences in mission and teaching statements. The workshop activity offered a unique experience to think about these differences and how I saw them play out in the education I received at each.

Prior to the CCT Institute I had not thought about looking at university teaching and mission statements much. The workshop showed me that doing so can help me gain clarity about what universities expect of me as an educator and can help me draft tailored teaching philosophy statements and cover letters when I go on the job market. By knowing what is expect of me as an educator, I am also able to design more effective learning outcomes. Sometimes this can be the most daunting task when creating a course: deciding what students need to know. By starting with an institution’s teaching and/or mission statements, I can “backwards design” my learning outcomes to ensure that students are accomplishing what the university sets for them.

As as separate kind of reflection on this topic, I have been studying Indigenous and decolonial theories as part of both of my programs, and I have been working with Indigenous communities on digital projects. Through these experiences I have learned that the use of the term “mission” is harmful because of its deep colonial roots. As a member of a project that is currently crafting a strategic action plan for a project by and for Anishinaabe community members and scholars, I have witnessed the negative response to this term. We decided to call our mission statement a purpose statement to avoid this colonial term. This experience will serve as a reminder that whenever I am looking at another institution’s mission statement, I should also look to see if they have a land acknowledgment and what other efforts they have made to be anti-colonial and take responsibility for its participation in colonialism. I specifically thank Dr. Gordon Henry for his influence on this portion of my reflection.

SOURCES: